This is a story of my childhood and the books I read. It tells you the great miracle of the revival of the Hebrew language. This little girl just arrived from Iran in Israel of the 50's and she has access to world literature translated to Hebrew. It also tells about a curious girl relating to stories about motherhood, childbirth, hygiene and bigotry.

The Hebrew Title:

זעקת האמהות - מורטון תומפסון

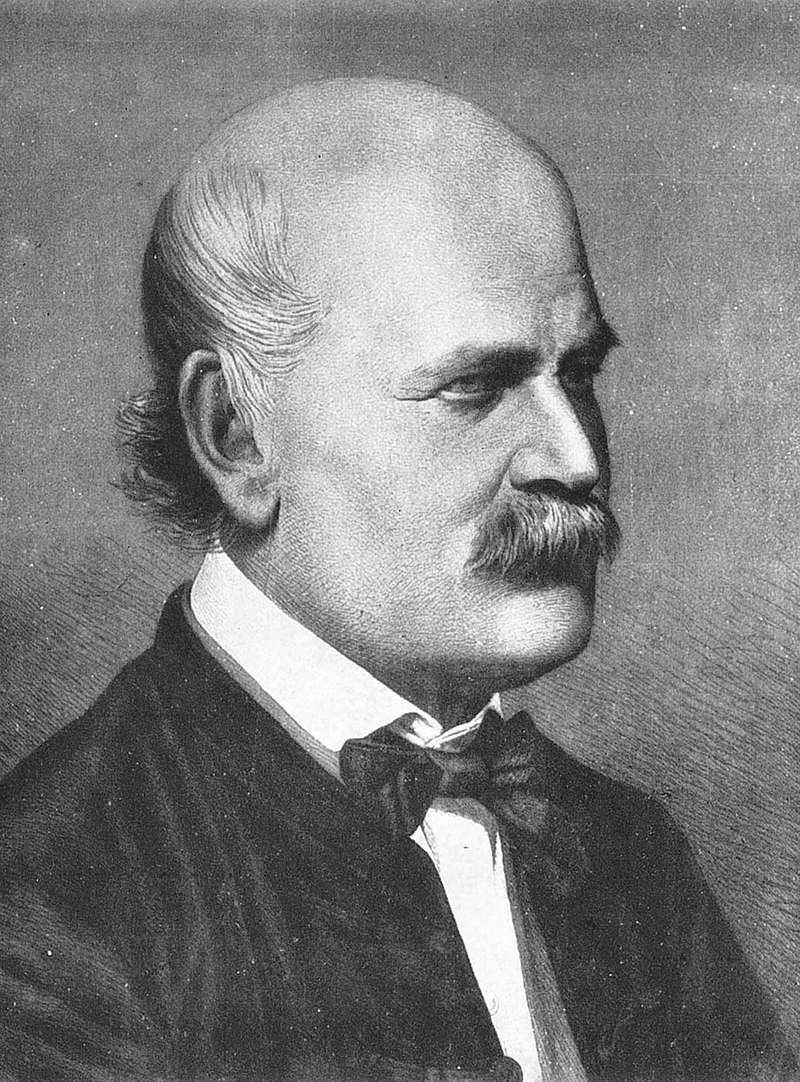

I was reminded of this story today while listening to my weekly radio program reviewing world press. The French magazine "Historia" has just published an article about the life of Ignaz Semmelweis.

Ignaz Semmelweis is a curious child who often gets in trouble at school for asking too many questions. As a young man, he travels from his native Hungary to Vienna to study medicine, becoming an obstetrician at the Vienna Lying-In (labor and delivery) Hospital. At that time, in the first half of the nineteenth century, European women giving birth are ravaged by puerperal fever, a form of bacterial infection, before the germ theory of disease or antibiotics were known. The hospital unit operated by the medical school for training physicians had triple the death rate of that of the unit run by the midwives. To find out why, Semmelweis embarks on a painstaking investigation. Without knowing the mechanism at work, he discovers that infection is spread from one patient to another by contact, facilitated by frequent patient exams made by the medical students. Over the resistance and ridicule of the hospital administration and staff, he develops and implements a strict practice of hand washing with disinfectant before every patient contact. This brings the hospital death rate down to practically zero. Even so, the hospital administration and general medical community refuse to adopt Semmelweis’s ideas or practice. Enraged at the medical establishment’s failure to save lives by this simple procedure, Semmelweis writes letters to medical journals accusing physicians of being murderers. Eventually, more and more overwrought by his frustration, he becomes unbalanced, passing out handbills in the street telling women to demand of their doctors that they wash their hands, and otherwise behaving so erratically that he is committed to an insane asylum, where, ironically, through a cut finger he contracts and dies of the very disease he spent his life fighting.

A legacy of Semmelweis, highlighted in The Cry and the Covenant, is that hand washing, to this day, remains the most effective method of preventing the spread of infection.

Semmelweis statue at the University of Tehran.

What a sad end to the life of a brilliant man!

We can blame those Viennese doctors who could not accept the fact that their hands were "dirty".

No comments:

Post a Comment